Parameterization

Introduction

To parameterize, or not parameterize, that is the question. Here the eternal question of data science is explored.

Developing Intuition

In a data science context, parameterization is the process of assigning parameters (sometimes called coefficients) to develop an approximation of a function. You will recall from the the Starter Guide on the meaning of f(x) in data science that the function $\hat{f}$ is an approximation of the actual function $f$, which is unknown. The nature of parameters change depending on the context; for instance, maybe you’ve seen parameterization done in a geometrical context, which might attempt to summarize a function in terms of a specific coordinate framework, like cylindrical polar coordinates ($\rho,\phi,z$).

One thing to note about parameters is that they are typically discovered; that is, we don’t assign them based off of intuition or optimization (this falls into the realm of hyperparameters, or tuning paramaters).

OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) As An Example Of Parameterization

OLS is a common example of a modeling technique that utilizes parameterization. You might even know that the $\beta$ values in

$ f(X) = \beta_0 + \beta_{1}x_1 + \beta_{2}x_2 + … + \beta_{p}x_p $

are the parameters of the general OLS equation. When we fit the model, we find the $\beta$ values which minimize the SSE (Sum of Squares of Errors). If the data ($X$) were to change slightly, this might result in different $\beta$ values. Once we’ve fitted the model, and found the parameters, we can build our $\hat{f}$.

The problem of estimating $f$ gets boiled down to finding a set of parameters to build our function with when using a parametric method.

Splines As An Example of Non-Parameterization

Splines are a great way to visualize non-parameterization. There are many ways to build splines (whole careers have been dedicated to such pursuits), but in general the idea is to make a direct line between all data points by making a piecewise polynomial between each pair of points.

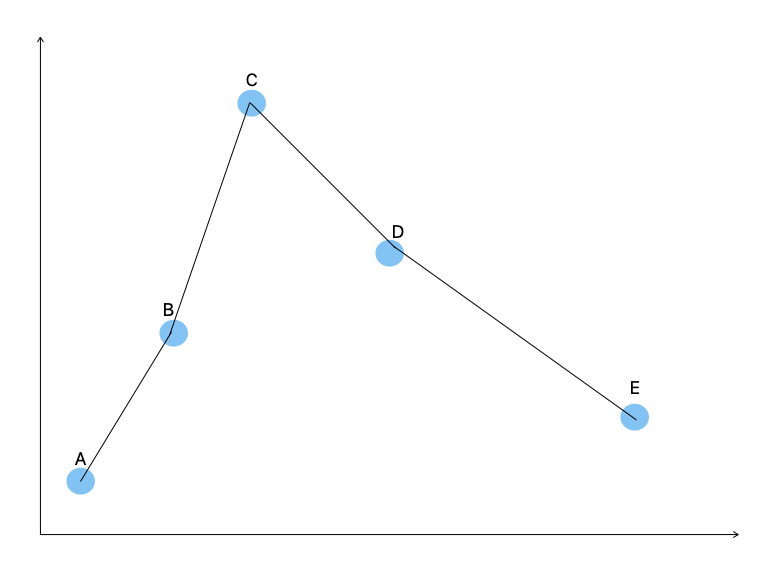

You might recall the picture of a very simple spline from the Starter Guide on the meaning of f(x) in data science.

We have 5 data points, represented by the blue dots. The black line is our spline, which we got by making a piecewise set of functions between points A to B, B to C, etc. We don’t need any parameters at all to build this piecewise function; the data itself will tell us what the function should be.

The attentive reader here will notice that a piecewise polynomial still has parameters. For instance, maybe the polynomial between points A and B is $2x+7$, where x is a parameter. In other forms of splines, such as cubic splines, a fitted curvilinear line that goes between all the points is also a polynomial. However, the difference is that the estimation of $f$ is determined from the data, then the polynomial (and thus what are in essence parameters like x) is created, rather than us finding what the parameters are, and building $f$ from there (as we would do in parameterization).

Why Would We Ever Not Parameterize?

One challenge with parameterization is that you have to make assumptions about the shape of $f$, and these assumptions can hinder the model fitting process by limiting the possible shapes that $\hat{f}$ can take. This is analagous to building on a vast open land, versus building in a dense city: although the convienences of life might be missing in a rural area, a city plot might be more limited in what you can build, and how you build it.

For those familiar with regression, often times there are basic tests done early on in the analysis to see if a simple linear model is ideal, or maybe interaction effects, or multivariable polynomial regression is more appropriate. Here, the analyst is trying to find out the form, or shape, $f$ might take, and lend the correct possibility of shapes to $\hat{f}$. But these are tests, intuition, guesses, sometimes well informed, other times just shots in the dark, but regardless of how certain we are of the shape of $f$, our choice of how we parameterize makes a difference.

By not parameterizing, we remove the possibility that we are way off in the shape of $f$.